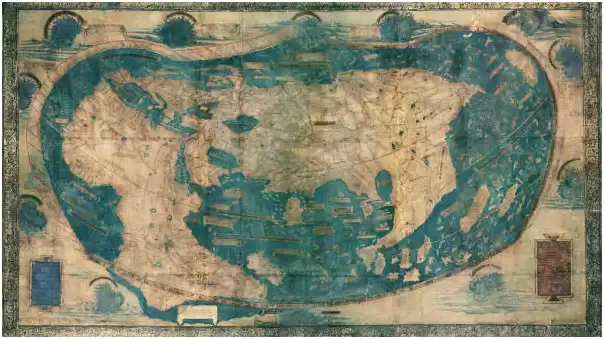

Rome (dpa) - The life of Christopher Columbus is awash with intrigue, mystery and controversy. Scientists from Italy and Spain now hope to solve at least one riddle: his country of origin. Geneticists from Rome's University of Tor Vergata and the University of Granada are collecting DNA samples among possible descendants living in Italy, Spain and France. The samples that will be found to be most similar to Columbus' DNA will determine his nationality.

Historians usually describe the great explorer as the son of a wool weaver from Genoa, a port city in modern-day Italy.

However, there exists a plethora of competing theories about Columbus' true origins. The man credited with having ”discovered” America in 1492 may in fact have been Spanish, French, Portuguese or even Greek. The different hypotheses are fuelled by the fact that little is actually known about the admiral's early days. In fact, historians do not even agree on his date of birth - which they place sometime between August and October of 1451. Experts note that Columbus himself was often secretive about his own past, suggesting he may have had something to hide.

”Columbus never provided any reliable proof about his origins and many useful documents have disappeared,” says Ruggero Marino, author of a number of two books on Columbus in which he claims Columbus was in fact the illegitimate son of Pope Innocent VIII.

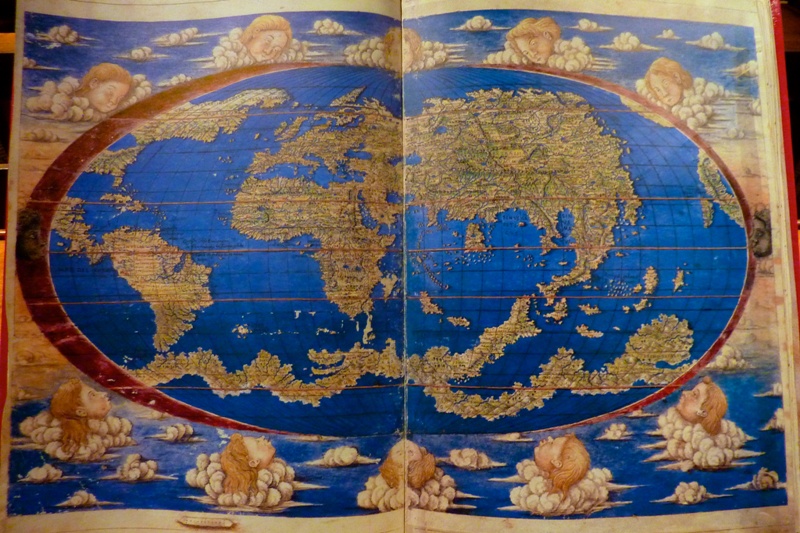

Supporters of the ”Italian theory” say Columbus' reticence probably had something to do with the fact that he preferred to conceal his humble origins while looking for financial backers among the kings and popes of 15th-Century Europe. Columbus was a self-taught cartographer who received virtually no formal education before becoming a sailor.

Sponsors of the ”Corsican theory” retort that Columbus may in fact have wanted to hide his Corsican heritage as the Mediterranean island - then part of the Genoese Republic - suffered from a bad reputation at the time. Similar arguments are used by those who claim he started as a pirate serving under the French corsair Guillaume Casenove Coulon and later took his surname.

The fact that Columbus usually spoke in Catalan rather than Italian gives strength to those who believe he was Spanish, perhaps a converted Jew who escaped the Inquisition. Others claim he was born in a small island in Catalunya's Ebro delta that was called Genoa.

Documents have been found that suggest he might have been Portuguese - Columbus lived in Lisbon in 1477 and married the daughter of a noble Portuguese family in 1479 - or even Greek.

Experts like Marino - who is a member of the Italian scientific committee for the Columbus celebrations - believe the explorer must have used a pseudonym as his name is just too curious to be true.

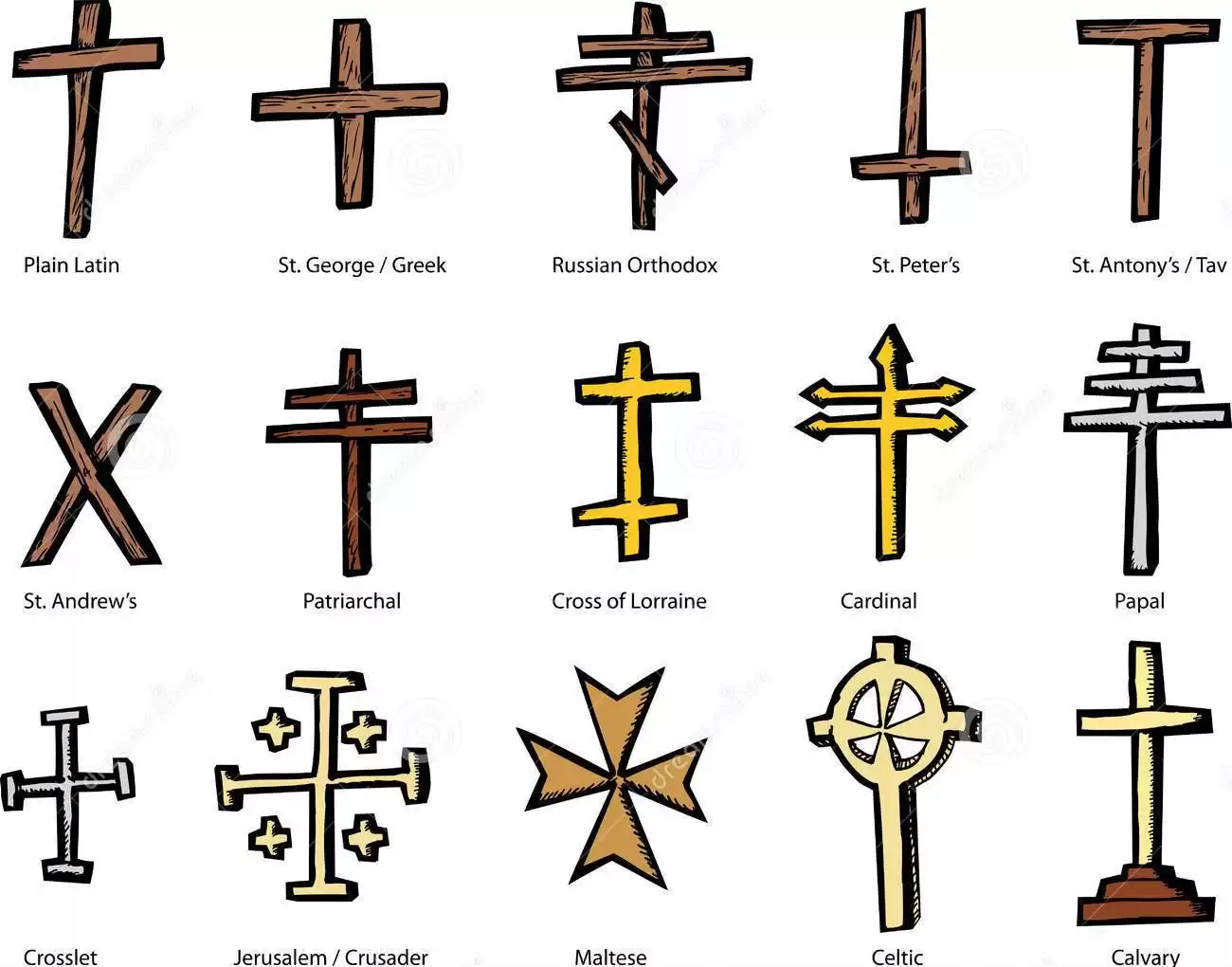

Cristoforo (in Italian) or Cristobal (in Spanish) derives from the Latin ”Bearer of Christ” while Colombo (Colon in Spanish) comes from ”dove,” a reference to the Order of Christ which initiated the age of exploration. The pseudonym theory is, however, dismissed by most historians.

This is good news for researchers in Rome and Granada as they are concentrating their efforts on Italians, French and Spaniards who bear the surname Colombo, Colon, Colomb or Coulomb.

The two teams have so far received dozens of saliva samples from Columbus' possible common ancestors and hope to have several hundreds in the coming weeks. The samples will then be compared to the DNA of Columbus' illegitimate son Hernando as the true location of the explorer's remains is still under dispute - some say he is buried in Seville, others on the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo.

”If we find a similar Y chromosome in Italy rather than Spain, for instance, we will be able to say with certainty that Columbus was Italian,” said Professor Olga Rickards, professor of Molecular Anthropology at Rome's Tor Vergata University. Rickards and her Spanish colleague Jose Antonio Lorente Acosta, who heads the Laboratory of Genetic Identification at the University of Granada, hope to end their studies by May 20th, when the 500th anniversary of the explorer's death will be celebrated. And while both researchers concede that their study may produce inconclusive results - if, for instance, the same chromosome is found in both Italy, Spain and/or France - they insist they are not in competition with each other.

”As a scientist, I am more interested in determining the facts,” said Rickards, only to add: ”Having said that, I wouldn't bet on Columbus being Spanish.”

One person who certainly does not want surprises is Genoa's mayor, Giuseppe Pericu. ”I have strong doubts about the usefulness of this kind of research. Firstly, I am not sure that DNA tests can always produce certain results. Secondly, I prefer to trust all of the authoritative historians who do not doubt Columbus' Genoese origins,” Pericu told Deutsche Presse-Agentur dpa. The city, which has monuments to Columbus and has even named its airport after the great explorer, is planning a number of events to mark the quincentenary of his death. Asked how he would react if it were to emerge that Columbus was, in fact, Spanish or French, Pericu said: ”It means we will have to adopt him as an honourary citizen.”